Citizen Science & Exploration

Citizen Science and Exploration

Jill Heinerth

For the last six years, I have been taking on exploration work that has pushed the limits of my academic background. While exploring Canada’s longest underwater cave system, I noted an exceptional community of filter-feeding organisms, unlike anything I have witnessed before. During visits to the Canadian Museum of Nature, I met with Dr. André Martel, a malacologist who studies freshwater mussels for the museum. With his guidance and mentoring, I plunged into scholarly papers to expand my knowledge of the benthic life. I joined his lab’s diving team, making trips to the Ottawa River to learn about biology firsthand and took on a contract with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans. As the only cave diver in Dr. Martel’s lab, I shared my observations from the caves about 120 kilometres west of Ottawa, Ontario. Through photography and surveys, I hope to explain how a mostly overlooked animal is a sentinel species that can teach us about the freshwater food chain’s interconnectivity.

Chains are only as strong as their weakest link. When an indicator species or group of species is in danger of extirpation from a given habitat or even global extinction, it behooves us to learn about its value before it is too late. I’m not talking about a large or charismatic species like a whale, dolphin, or seal. Studying big marine mammals gets much more attention. I’m talking about species that you may have only valued on a dinner plate, bathed in garlic butter - a simple mussel – although the ones I study with Dr. Martel’s team are those inedible freshwater mussels found in rivers and lakes. Even the habitats where freshwater mussels live are not particularly appealing to divers. The Ottawa River is known to have reduced visibility, generally under one metre. Not many scuba enthusiasts explore the current-swept tannic depths of this large river. For me, documenting mussels means dragging a lot of gear into a small, high-flow, silt-ridden cave that seems like a claustrophobic nightmare to most.

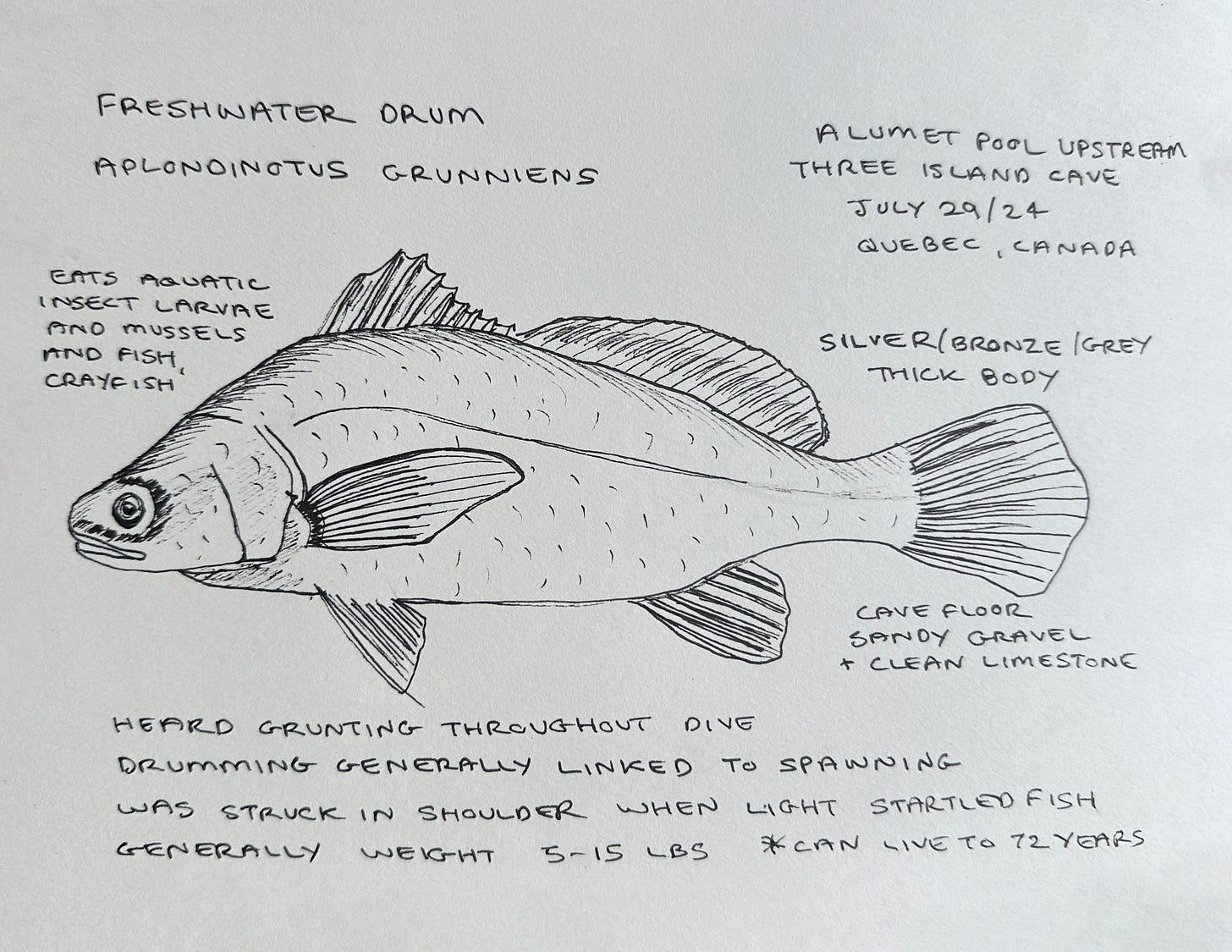

Freshwater mussels are bivalves, sometimes called river mussels or unionid mussels. They burrow into a silty, sandy, or gravely bottom substrate, obtaining food and oxygen by pumping water through an incurrent aperture and expelling waste and filtered water through the excurrent aperture. As filter feeders, they remove plankton, bacteria, fungi, and other organic material from the water. They differ from their marine relatives, anchoring themselves on rocky substrates in the ebb and flow of ocean tides. Canada’s native freshwater mussels, those living in rivers, live in a linear, mostly downstream, world, facing dramatic changes in seasonal water temperature, water level, and currents.

In the late 1980s, when André Martel was a Ph.D. student, an invasion of non-native and highly invasive Zebra mussels swept into the Great Lakes Watershed. Few predicted that those invaders would dramatically change the ecosystem. As divers, Dr. Martel and I have noted visibility improve from a couple of meters to sometimes thirty or greater today in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. But the Zebra and their brethren, Quagga mussels, are unwelcome guests. They have harmed the Great Lakes ecosystem, river, and lake habitats as invasive species. The water may look more transparent, but the benefits end there. Non-native marine mussels like the Zebra and Quagga throw everything out of balance, even promoting toxic algal blooms because of their dietary planktonic food preferences. In sharp contrast, native freshwater mussels live in harmony with the natural ecosystems where they live, filtering the plankton and not throwing the planktonic food web out of balance. A native mussel can filter 1 to 3 litres per hour or over ten metric tons of water per summer. Depending on the species, they may live as long as 20 to more than 100 years, quietly filtering and ingesting food particles out of the water column, including phytoplankton, detritus, and even coliform bacteria, something that the invasive Zebra and Quagga mussels do not provide as an ecosystem service. Native freshwater mussels can even reduce heavy metals, flame retardants, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides from the water.

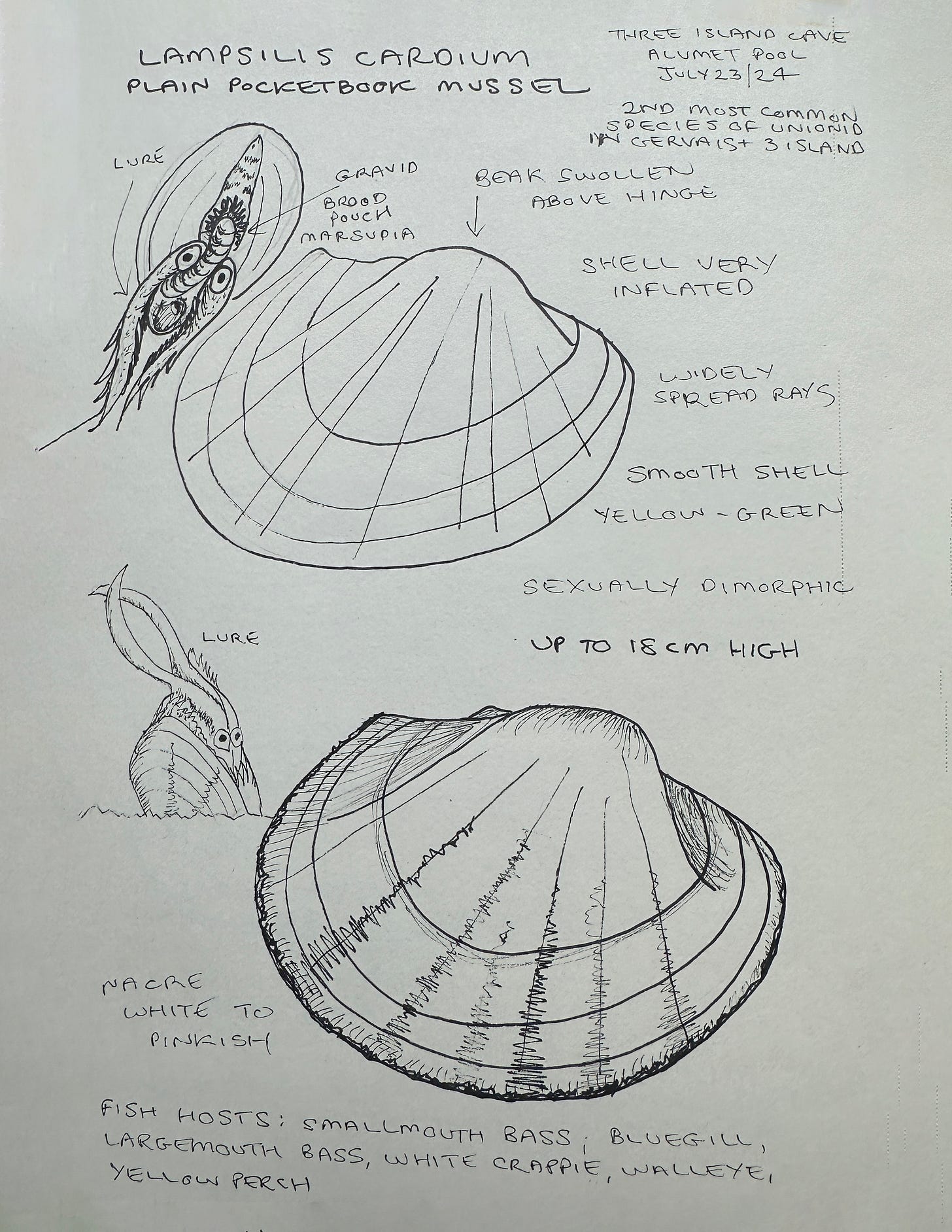

The native mussel species living inside the Gervais/Three River Caves of the Ottawa River seem to thrive in isolation despite their unique reproduction requirements. They cannot survive without the help of local host fishes living inside or passing through the caves, swimming in and out through swift currents. The sex life of a native unionid mussel is exceptionally complicated. A male ejects sperm that floats downstream to a female. She releases fertilized eggs from her single ovary into specialized compartments of her gills called marsupia. The young develop into a microscopic, hinged, specialized larval form called glochidia.

Meanwhile, female mussels such as the Plain Pocketbook, Lampsilus Cardium, grow a unique “lure” that protrudes from her shell in the shape of a small fish, complete with markings, fin-like structures, and spots that look like eyes. She flexes her decoy-like lure to attract specific fish species. When a fish gets close, she expels the glochidia that snap onto the gills of an immature host fish. After attaching to the fish’s gill filaments, the glochidia encyst and remain inside for weeks or months, the fish’s hemolymph providing them with a food source. The juvenile host fish carries the parasitic mussel babies until they mature enough to excyst and bury themselves in the bottom, where they will further develop for a couple of years before re-emerging. The relationship does not harm the young fish, but if the glochidia attach to an older fish, they will be expelled or rejected by the fish’s immunological defence system. The odds of completing this life cycle are slim and made even more unlikely in the face of stressors such as reducing the number of their host fish, water pollution, and siltation. The Hickorynut mussel, one of the species of native unionid mussels found inside the caves, is an endangered species. Its presumed host fish is the Lake Sturgeon. If we lose the sturgeon, we will likely lose the Hickorynut mussels.

Dr. Martel’s work and other malacologists, naturalists, and volunteer divers now reveal that the Ottawa River watershed is home to roughly 38% of Canada’s mussels (21 of 55 surviving species). Luckily, there are no invasive Zebra or Quagga Mussels in a 141 km long stretch serving the cave passages near Westmeath, Ontario. Native mussels, our natural water filters, are imperiled by many things, including habitat loss, pollution, dams, viruses, bacteria, and non-native species. These unappreciated animals offer remarkable ecosystem services beyond filtration. The animals provide high-value services as a part of the natural food chain, a micro-habitat, and a supporter of resilient nutrient cycles. A human-engineered equivalent would be neither cost-effective nor as efficient as the natural collaborations in the Ottawa River.

By protecting these native species, we buy ourselves time to fully understand their value and potential to contribute to habitat improvement, sustainable food sources, and environmental mitigation/sanitation. My work and storytelling will better prepare us to engage in system-wide solutions for protecting precious habitats.

Robert’s Audio Essays

When we lived in Florida Robert worked as a contract nurse for the Department of Corrections - A Prison Nurse. It was at times a challenging and chaotic atmosphere looking after the physical and mental health of inmates at Florida State Prison and Union Correctional Institution. From Robert’s book “Boom Baby Boom” - Have a listen:

Jill has a special relationship with the Ottawa River. She is the 2024 honourary Ottawa Riverkeeper, and her work takes her in, above, and below the surface. The Ottawa is also a world-class whitewater kayak and rafting destination. It can get wild out there:

Roughing It Smoothly

Robert and I went for a short hike on the Tip to Tip trail that runs along the Rideau Canal near the small village of Burritts Rapids. As part of Parks Canada, we found a set of iconic red Muskoka chairs along the way - a great place for a mid-trek picnic!

New Feature - Private Chat.

We just kicked off a new chat feature here on Substack. Everyone can participate, and for now, Paid Subscribers can start threads. All topics welcome - this is a safe, free speech zone. You should have received an email with a link to the chat feature. Let’s get to know one another.

Sidewalk Chalk Wisdom - Classy graffiti around the corner from our place.

“With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come…”

I remember reading before about those fresh water bivalves and their complicated life cycle. I am blown away by their longevity! It may be their saving grace since they depend on so many conditions to successfully reproduce and reach maturity. I am so grateful to people that choose to study those seemingly insignificant species, it gives us a chance to at least be aware and then we learn just how significant they actually are!

I also remember you talking about diving in that tannic color water in the caves under Ottawa river and watching you flip one and how it straightened itself out!

Fascinating read! Learning more every day and also helps me stay sane here in California as we navigate this crazy election season! Yours is a safe and positive space!