Sometimes, it is fun to dig into the archives and share an expedition story that has come to the front of my mind. I have had the privilege of working with the team from Stone Aerospace over the decades—from driving the first 3D underwater mapper in the 1990s to seeing the device fully realized as an autonomous, artificially intelligent robotic underwater surveyor. Just before COVID rang around the world, I was on a vessel in California, mapping former sea levels and ancient caves. - Jill Heinerth

SUNFISH: An autonomous, artificially intelligent sonar mapper that swims itself into and through the cave, returning when it gets low on power. Detailed point cloud data is assembled in real time with high resolution output rendering after the mission is completed. Depth Rating 1000+ feet. Air Weight: 75 lbs.

Mapping Ancient Caves

Robert Ballard, the explorer who found the RMS Titanic, smacked me between the shoulders with a rolled-up magazine. He chuckles triumphantly, “I got it!” The flies off the California Coast are swarming us, and Bob is doing everything he can to personally put a dent in the population. Camera in hand, I’m here documenting a gathering of engineers, scientists, and explorers for a collaborative project sponsored by Ballard’s Ocean Exploration Trust and National Geographic. On the charter boat, PEACE, are computers, lasers, sensors, and an artificially intelligent robot. Fibre-optic cables are strung out from above, and rebreathers and assorted diving gear litter the deck. Undoubtedly, the vessel’s payload of life support equipment, 3D scanners, and cameras is valued more than the boat itself. Ballard is smiling from ear to ear, leading the troops enthusiastically while swatting flies and passing out a feast of Trader Joe’s gourmet snacks for support. At 77 years of age, this is his 140th expedition. Ballard’s projects are all connected, whether finding Titanic, searching for Amelia Earhart’s plane, or showing school kids live footage of marine life clustered around deep ocean vents. The technology he uses on one expedition builds capabilities for another. This modest mission in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary will offer rewards for future projects well beyond its borders. With better maps of the world’s oceans, researchers can protect dwindling fish populations, find valuable mineral resources, protect ships, establish sovereign territories, and even test equipment proficiency for missions beyond Earth. But all this technology won’t do a thing to combat the incessant flies.

We’re in the Channel Islands to examine an offshore region called the California Continental Borderland. In this area, caves were carved by the ocean in the period since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) about 19,000 years ago. Over a series of dry times on the planet, the sea levels paused long enough to create shelf-like, paleo-shorelines, or “stands.” At depths of 120, 110, 100, 70, 35, and 10 meters below the present sea level, the water level stopped fluctuating long enough to permit ocean surges to form wave-cut ledges and caves. The sea caves likely started as a crevasse or fissure that was exploited by the pounding action of the surging water. Scientists hypothesize that humans could have inhabited some of these caves after leaving Beringia to populate the rest of the Western Hemisphere (e.g., Erlandson et al., 2011; Reeder-Myers et al., 2015). Currently, the earliest human settlement in western North America is represented by a time when the sea levels were 35 meters below present. Finding evidence of human occupation in caves below 35 meters could broaden the story of human migration.

However, documenting paleo shorelines of a much larger continental North America is only one of the project’s lofty goals. These caves offer an opportunity to assess and improve digital mapping technologies. Our team seeks to increase the range, accuracy and speed of new survey devices, which is the perfect proving ground. Deploying rebreather divers to map a cave traditionally takes time, requires ideal weather, and presents an envelope of risk, especially when the dives are deep. Ballard is looking at the most innovative and versatile mapping platforms to document these caves quickly and plans to use these devices on deeper, more remote expeditions.

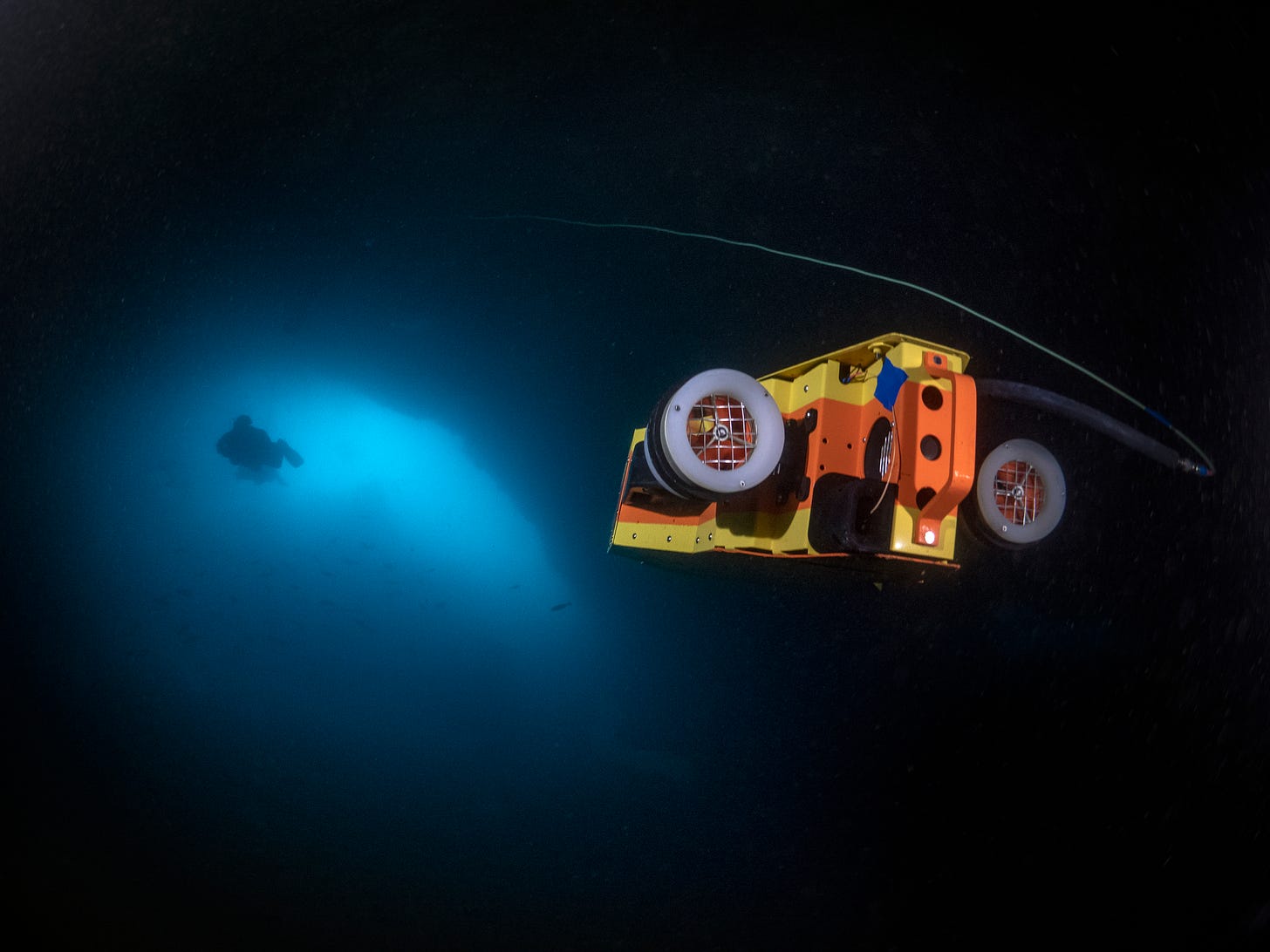

A stiff wind stirs the sea while cave-diving explorers Cristina Zenato and Kenny Broad prepare their rebreathers. Aerospace Engineer Kristoff Richmond waits at his keyboard while his programming partner breaks to barf up their breakfast. The ocean swells build to a crescendo, and we watch a white foamy spray explode from the doorway of a cave on Santa Cruz Island. It is a race to get in as many dives as possible before the escalating surge makes it impossible to dive the cave safely. Every wave stirs up a roiling mess of silt that obliterates the visibility, and worse, the swell amplifies in the narrow tunnel, pressurizing the cave with a battering ram of seawater that feels like it is crushing our tender ears and sternums. I and others have been sick underwater, in the cave—the relentless rocking and pressure change simply too much to bear. On this dive, we follow the Sunfish autonomous, artificially intelligent (AI) mapper (Here’s a video link.) past kelp fronds and garibaldis into the open maw of the cave. A curious California sea lion darts past my camera, glancing sideways at the orange and yellow robot that has just found a doorway into the labyrinth beneath the island.

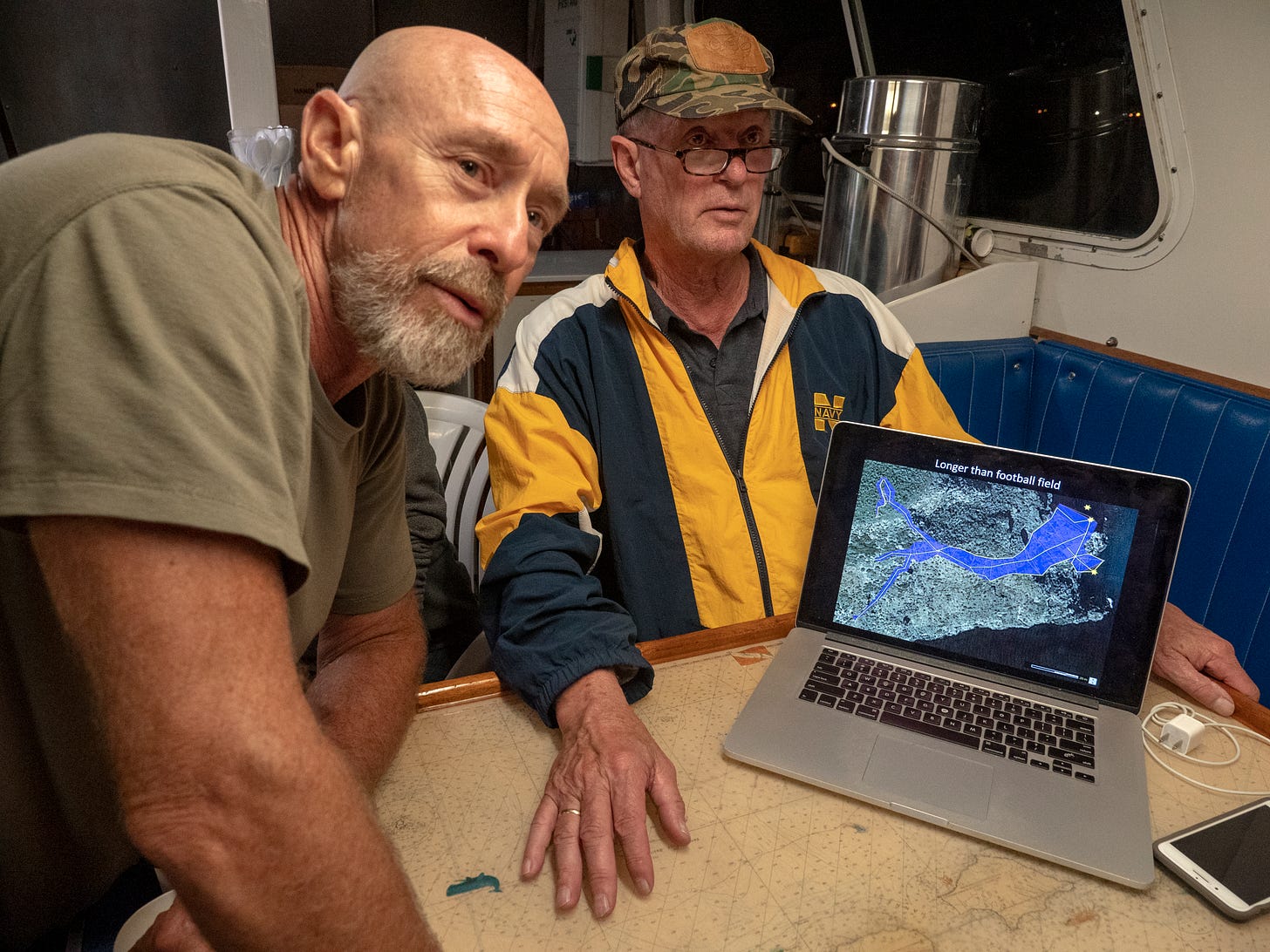

This morning’s goal is to navigate into the cave, make a 3D map and return, using only an AI brain for guidance. The mapper drives itself while engineers watch over its shoulder via a fibre-optic cable attached to its stern. Our dive team stays close if we need to gather up the optical fishing line spooling from behind. It is almost surreal to watch Sunfish pause, spin with its thrusters, and apparently “think.” Hovering in place for a moment, it suddenly springs to life to decisively launch forward, blasting sonar at the walls to stockpile a spray of measurements. Stopping again, it rotates in place to fill in the blanks of its knowledge and send the imagery back to Richmond onboard PEACE. Ballard watches over his shoulder, narrating the mission like a sportscaster, already envisioning what we might be able to achieve next. He’s already asking people about their availability in the coming months.

In another corner of the galley, MIT post-doc Jake Bernstein is tinkering with a hand-held device called Prometheus. A diver will pilot his LIDAR-like mapper to achieve a similar result as Sunfish without expense. It is one of many new devices built by MIT’s Future Ocean Lab. They aim to create affordable, high-tech tools for ocean exploration and research. He’s struggling with a leak in his prototype. Three other engineers are offering duct tape, paper towels, and Aquaseal© to return it to the water. I guess that is the universal solution to fixing anything. If successful, this device will fire laser pulses several million times a second at the cave walls and measure the return speed. Rather than sonar-generated data points fused into a cloud with the help of inertial measurement chips and cameras, light should produce an image of the cave walls in glorious detail.

Across from Bernstein, Sebastien Kister vies for the last real estate of table space for his laptop. He is merging a volumetric model of the cave that was produced by his MNEMO device with the data stream from Sunfish. His low-tech, diver-held instrument is an advanced guideline measuring tool a cave diver uses to run and survey their exploration line. Small enough to fit in a diver’s drysuit pocket, MNEMO’s data appears to correlate well with the advanced code coming out of Sunfish. The two maps align, and Kister sports a rare victorious smile.

Although united in the mission to map this cave accurately, we all understand that our ultimate goal is to make ourselves obsolete. We need to remove the human element and reduce risk to rapidly and precisely map the world’s oceans and caves. For now, our jobs are safe. There are many deeper caves to explore, and now that we have passed this hurdle, we will return to document and test the gear in new unexplored places. These protected ancient sea caves within the tech-diving zone have not been disturbed since the last ice age. With the potential to hold clues about human history, they are literal time capsules awaiting our exploration.

Channel Islands Diving Info

Kelp forests, caves and coves within the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary are best accessed via Santa Barbara, Oxnard and Ventura. Extreme winds often create large swells, requiring excellent diving skills and comfort in surge and high seas. Anacapa and Santa Cruz Islands are the most popular diving spots with garibaldis, bat rays and sea lions sure to offer a show. Colorful anemones, sponges and starfish carpet the rocks, while octopus and lobsters are usually hiding nearby.

Water temperature varies from 50°F in the winter to 70°F in the summer. Visibility can be a greenish 30 feet up to 120 feet. When swells create surge, the visibility in the sea caves can quickly degrade to zero. Cave diving is only for extremely experienced individuals with proper training and experience in high surge and low visibility conditions.

And Now…A word from early morning, one cup of coffee short Robert:

If you haven’t figured it out, Robert McClellan is an accomplished writer and had an early career as a highly commended US Navy photojournalist. He never lost his love for storytelling and has written three books since retiring from the military. He will share some of his essays and experiences from all aspects of life. Who doesn’t love a good story? Here’s one from his book “Boom Baby Boom.”

Dirty Frank’s and the Thirsty Pope

It is a big day in Philadelphia. The Pope is coming.

Sitting in Dirty Frank’s bar on Pine street, I am drinking cold Rolling Rocks and watching the local news anchors cover the motorcade as it winds its way through South Philly and up Broad street. I am on a rickety old barstool, only a block away from the main route. My buddy Joe insisted that we leave the hot, humid apartment we share, and seek sanctuary in Frank’s cold beer and cool air conditioning.

The TV screens hung precariously in corners of the bar show throngs of enthusiastic people lining the streets blessing themselves with the sign of the cross, as the popular pope smiles and waves to his faithful flock.

As the newscasters announce that the motorcade is approaching, a half-dozen of us decide to run over to Broad street to witness history, the holy Pontiff's visit.

There are thousands of people, crammed three and four deep, on the sidewalk here in the center of this heavily catholic city. I elbow my way to a front-row position and press against the yellow wooden police barrier that separates us from the great infallible spiritual leader.

As his convertible limo slowly drives by, I raise my green pony bottle in an exaggerated toast to His Holiness. I think he winked at me - and sweating under layers of papal robes, he probably wished he could join us to chug a cold one down.

The excitement is over quickly and I jog back to Frank’s, reclaiming my seat and ordering another beer.

Unknown to me at the time, it will not be the last time I see Pope John Paul II in person.

I am such a fallen catholic. Thank God

We appreciate you taking a few minutes each week to explore our newsletter. As Robert said in the video above, please feel free to comment and even make suggestions. I read and try to respond to every single one. Cheers, Jill

That is just wild! Just mind blowing what technology designed by some really brilliant human beings can do! Can I have one to be my dive buddy? I would never be afraid of getting lost underwater ever again! 🤣🤣🤣! Seriously, for science and data collecting that is priceless!